What Makes a Country Bad for Again

Abstruse

This chapter discusses the reasons why countries develop or remain poor. It examines the many reasons advanced for this and provides fresh perspectives on historical experience and the bookish literature. It looks both astern over the past seventy years and frontward to consider new factors shaping the development of nations and the roles of businesses, governments and individuals everywhere.

This affiliate draws extensively on Ian Goldin, The Pursuit of Development: Economic Growth, Social Modify and Ideas, Oxford University Press, 2017. Readers are referred to the book for the full references and for recommendations and farther reading.

1 Introduction

How individuals and societies develop over time is a key question for global citizens. Likewise many people in the globe still live in extreme poverty. Near one billion people live on less than $i.25 a 24-hour interval (the Earth Bank'south definition of extreme or accented poverty) while about 2.2 billion people live on less than $2 per day. What can be done near this?

Development Studies as an bookish discipline is relatively new, simply the questions being asked are not—philosophers have puzzled over them for millennia. There are many definitions of evolution and the concept itself has evolved rapidly over recent decades. To develop is to abound, which many economists and policy-makers have taken to mean economic growth. Yet development is not confined to economic growth. Development is no longer the preserve of economists and the subject itself has enjoyed rapid evolution to become the subject of interdisciplinary scholarship drawing on politics, sociology, psychology, history, geography, anthropology, medicine and many other disciplines.

two Why Exercise Some Countries Develop and Others Not?

A hundred years ago, Argentina was amongst the seven wealthiest nations in the globe, but now ranks 43rd in terms of real per capita income. In 1950, Ghana's per capita income was higher than that of South Korea; at present Southward Korean people are more than 11 times wealthier than the citizens of Republic of ghana. Meanwhile, more twenty failed states and over a billion people have seen trivial progress in development in recent decades, whilst over three billion people have seen remarkable improvements in health, education and incomes.

Within countries, the contrast is fifty-fifty greater than between countries. Extraordinary achievements enjoyed by some occur aslope both the absolute and relative impecuniousness of others. What is truthful for advanced societies, such every bit the Britain and U.s., is even more then in nearly, but not all, developing countries.

Many factors accounting for the successes and failures in the extreme unevenness of development outcomes. There is an all-encompassing literature which seeks to explicate outcomes on the ground of natural resource endowments, geography, history, cultural or other.

Overall, the bear witness points to divergence—rather than convergence—in recent decades, although there is some variation amongst geographical sub-groupings, with a ready of Southeast Asian economies (the "tigers") displaying evidence of convergence. In 1993 Parente and Prescott studied 102 countries over the period from 1960 to 1985. They plant that disparities in wealth between rich and poor countries persist, despite an average increase in incomes, although in that location is some evidence of dramatic divergence inside Asia, which is consistent with some Southward East Asian economies—Nippon, Taiwan, South Korea and Thailand—catching up with the West. Li and Xu, have highlighted the extent to which the existent incomes of 7 Southward East Asian economies have grown 3.5 times (Malaysia) to 7.6 times (Communist china) faster than the United States and the G10 economies for the menses from 1970 to 2010.

The World Bank attributed the "East Asian Miracle" to audio macroeconomic policies with limited deficits and low debt, loftier rates of savings and investment, universal primary and secondary education, low taxation of agriculture, export promotion, promotion of selective industries, a technocratic civil service, and authoritative leaders. However, the Banking concern failed to highlight the extent to which the achievements came at the expense of ceremonious liberties, and that far from being free markets the governments concerned subjugated the market (and suppressed organised labour), often with the generous support of the United States and other evolution and military machine aid programmes, following the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

Others have argued that S East Asia's relative success had more to do with pursuing strategic rather than "shut" forms of integration with the earth economic system. In other words instead of opting for unbridled economic liberalisation in line with the Neo-Classical market friendly approach to evolution, countries such as Japan, Due south Korea and Taiwan selectively intervened in the economy in an try to ensure that markets flourished. Several well-known commentators including Ajit Singh, Alice Amsden and Robert Wade have documented the full range of measures adopted by these countries, which appear to institute a purposive and comprehensive industrial policy. These measures include the utilize of long-term credit (at negative existent interest rates), the heavy subsidization and compulsion of exports, the strict control of multinational investment and foreign disinterestedness ownership of manufacture (in the instance of Korea), highly active technology policies, and the promotion of large scale conglomerates together with restrictions on the entry and exit of firms in primal industrial sectors. The relative contribution of selective forms of intervention on the 1 hand, and market place friendly liberalisation and export orientation on the other, to the success of the South East Asian economies remains a bailiwick of debate.

two.i Poverty and Inequality

Income measures are only one dimension of poverty. Other indicators, including those relating to baby and kid mortality, illiteracy, communicable diseases, malnutrition and schooling are also important. A number of countries have made extraordinary strides in overcoming poverty. In some, progress has been beyond the board, whereas others have managed to achieve very significant progress on one dimension but fallen dorsum on others. With similar levels of average per capita incomes, in Bangladesh average life expectancy is 71, whereas in Zimbabwe information technology is 60 and in Tanzania it is 61.

Inequality between countries and within countries requires an analysis which goes beyond the headline economic indicators. While boilerplate per capita incomes are growing in most countries, inequality is also growing almost everywhere. The globe's richest 20% of people account for three quarters of global income and consume about 80% of global resources, while the world'southward poorest 20% consume well under 2% of global resources. Where poor people are is also changing. Xx years ago over 90% of the poor lived in low income countries; today approximately iii quarters of the world's estimated ane billion people living on less than $1.25 per day alive in middle income countries.

ii.two Explaining Different Development Trajectories

Every country is unique. Nevertheless it is nonetheless possible to identify a range of factors that bear on development trajectories. A number of economical historians have shown that patterns of resource endowments can reinforce inequalities and favour elites, with this in turn leading to "capture" and predatory institutional development. The resources curse has been examined by Paul Collier (2007), Jeffrey Frankel, and others, who have shown that aplenty endowments of natural resources may be linked with stunted institutional development, peculiarly in the instance of mining and oil. In mining and oil multinational or local investors have often operated behind a veil of secrecy. The awarding of contracts for extractive industries provides a source of power and patronage to corrupt leaders. Testify of abuse by international firms who take made offshore payments through international banks provides a clear example of how both avant-garde and developing countries have a responsibility to clamp down on corrupt practices, non least in mitigating the risks associated with the extraction of natural resources.

For the classical and neo-classical economists, as well as their critics on the Left, natural and homo resource endowments were a key determinant of trade and market integration. While the old group argued that revealed comparative advantage would lead to development, the critics argued the reverse, concluding that it would atomic number 82 to more than uneven development. Both groups saw international trade every bit a critical determinant of growth, explaining the convergence (or difference) of growth rates and global incomes, with Dani Rodrik, Jeffrey Sachs and Andrew Warner, Jeffrey Frankel and David Romer, and David Dollar and Aart Kray contributing alien prove of the relationship betwixt trade and development.

Jared Diamond, Jeffrey Sachs and others explicate evolution outcomes by providing geographical explanations. They contend that moderate advantages or disadvantages in geography can lead to large differences in long-term economic performance and that poor economic functioning can exist explained in terms of the "bad geography" theses. Geography is thought to bear on growth in at least iv ways. Firstly, economies with coastal regions, and easy access to ocean merchandise, or nearby big markets accept lower transport costs and are likely to outperform economies that are distant and landlocked. Secondly, tropical climatic zones face up a college incidence of infectious diseases, and malaria, bilharzia and other parasitic infections which hold dorsum economic operation by reducing worker productivity. For example, in 2015, malaria caused an estimated 438,000 deaths mostly among sub-Saharan African children. In add-on, a high incidence of illness tin enhance fertility rates and add together to the demographic burden of a country. Thirdly, geography affects agricultural productivity in a multifariousness of ways. Grains are less productive in tropical zones, with a hectare of land in the tropics yielding on boilerplate around one-third of the yield in temperate zones. Fragile soils in the torrid zone and extreme atmospheric condition are function of the explanation, every bit is the higher incidence of pests and parasites which damage crops and livestock. Fourthly, equally the tropical regions have lower incomes and crop values, agri-businesses invest less in tropical regions, and national enquiry institutions are similarly poorer. The implication is that international agencies, such as the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Enquiry (CGIAR)—which is donor funded—have a particular responsibility to raise the output of tropical agriculture. A similar signal can exist made with respect to tropical diseases, with depression purchasing power holding back evolution of drugs to gainsay many of the most significant tropical diseases.

William Easterly and Ross Levine besides as Rodrik and others, accept argued that the impact of geography is regulated through institutions and that proficient governance and institutions can provide the solution to bad geography. For example, good governments tin build efficient roads and irrigation systems, and invest in vital infrastructure too every bit enforce legal contracts and curb abuse. In short, good governance minimises uncertainty and transaction costs and can overcome bad geography. However, bad governance does non. For Easterly there are too many "Ifs, buts and exceptions" to Sachs' bad geography thesis. Subversive governments rather than destructive geography may as well explain the poverty of nations.

Rodrik and others debate that it is the quality of institutions—holding rights and the rule of constabulary—that ultimately matters. In one case the quality of institutions is taken into account (statistically "controlled for" using econometric techniques), the upshot of geography on economic evolution fades abroad. Still, every bit Rodrik notes, the policy implications associated with the "institutions rule" thesis are hard to discern and probable to vary co-ordinate to context. This in part is because institutions are partly endogenous and co-evolve with economic operation. As countries become better off they have the chapters to invest in more education and skills and better institutions, which in turn makes them better off.

For Daron Acemoglu, Smon Johnson and James Robinson, the development of institutions which facilitate or frustrate development, are rooted in colonialism and history. These authors fence that contemporary patterns of development are largely the consequence of dissimilar forms of colonialism and the mode in which particular countries were, or were not, settled over the past 500 years. The purposes and nature of colonial rule and settlement shaped institutions which have had lasting impacts. In countries with high levels of disease, loftier population density, and lots of resource, colonial powers typically fix up "extractive states" with limited property rights and few checks against regime power in guild to transfer resources to colonizers, such as was the case in the Kingdom of belgium Congo. In countries with low levels of disease and low population density, simply also less easily extractable resources, settlement was more desirable and colonial powers attempted to replicate European institutions—stiff property rights and checks on the corruption of ability—and made an effort to develop agronomics and industry as was the case in Canada, United states, Commonwealth of australia and New Zealand. According to this thesis, the legacy of colonialism led to an institutional reversal that made poor countries rich, and rich countries poor.

Although we may well alive in a world shaped by natural resource endowments, geography, history and institutions, politics and power can still play a decisive role in terms of driving economic performance and determining vulnerability to poverty. In Amartya Sen'south Poverty and Famines, he showed that political power and rules that are embedded in ownership and commutation determine whether people are malnourished or have adequate food, and that malnourishment is not mainly the consequence of inadequate food supply. Sen shows how droughts in North Africa, Bharat and China in the nineteenth and Twentieth centuries were catastrophic for social and political reasons, with ability relations, not agronomical outcomes, leading to widespread starvation and destruction of the peasantry. In 1979, Colin Bundy, in The Ascent and Autumn of the S African Peasantry was among a new wave of historians who argued that colonialism led to the deliberate collapse of a previously thriving domestic economy. In 1997, Jared Diamond's, Blood, Germs and Steel, while emphasising the importance of geography and history, showed how applied science, civilization, illness and other factors led to the devastation of native American and other previously thriving communities. These authors, echoing Marx, highlighted the extent to which evolution tin can be a very bloody business, even if the longer term consequences may exist to bludgeon societies into a new era.

If the abuse of power can set development back, what about the counter argument that democracy leads to more than rapid and equitable evolution outcomes? Co-ordinate to Irma Adelman, the long-term factors governing the association betwixt evolution and republic include the growth of eye classes, increment in quantity and quality of education, urbanisation (including more than infrastructures), the demand for participation in development strategies, and the need to manage the psychological and social strains arising from change. Acemoglu, Robinson and others went farther in 2014, arguing that commonwealth does crusade growth, and that it has a significant and robust positive result on Gross domestic product. Their results suggest that democracy increases futurity Gross domestic product by encouraging investment, increasing schooling, and inducing economical reforms, improving public practiced provision, and reducing social unrest. The difficulty of defining commonwealth, and the weight attached to the not-democracies which have enjoyed very rapid growth, such as China and Singapore, as well as the slowing of growth and paralysis in decision making in many parts of Latin America, Europe and other democratic regions means that the academic jury remains divided on the relationship between evolution and democracy.

3 What Can Exist Washed to Advance Development?

Peace and stability are essential for development every bit conflict and war leads to development in reverse, destroying not only lives, but too the infrastructure and cohesion which are fundamental to evolution. Literacy and education—and particularly the part of didactics for women—are vital, not least in overcoming gender inequities. The literature shows that these are cardinal contributors to declining fertility and improved family unit nutrition and health. Infrastructure investments, particularly in clean water, sewerage and electricity, as well every bit rural roads, are essential for growth and investment, as they are for achieving improved wellness outcomes. The rule of law and the establishment of a level playing field, through competition and regulatory policies are vital for ensuring that the private sector is allowed to flourish. The capturing of the market by monopolies or modest elites, often with the connivance of politicians or civil servants, is shown to lead to the skewing of development and growing inequality.

No country is an island economically and the way that countries engage with the rest of the globe is a key determinant of their development outcomes. The increasing integration of the world, in terms of financial, trade, aid and other economical flows, too as health, educational, scientific and other opportunities requires an increasingly sophisticated policy capability. So too does the management of the risks associated with increased integration into the global community. The threat posed by pandemics, cyberattacks, financial crises and climate change and other global developments could derail the best laid development efforts. Systemic risks accept a particularly negative impact on development outcomes, and without exception tend to have negative distributional consequences. The existence of constructive policies, or their absence, shapes the harvesting of the upside opportunities and mitigation of the risks.

3.one Literacy, Education and Health

At that place are both theoretical and empirical reasons for believing that literacy and didactics are essential for economic and social evolution. The education of girls has served to reduce widespread gender inequalities and has improved the relative position of women in poor countries. The education and empowerment of women has been associated with improvements in a range of development outcomes, and is associated with precipitous falls in infant mortality and fertility.

The links betwixt education, health and development are many and varied; in many contexts "all adept things" (or "bad things") get together. The demographic transition describes how fertility and mortality rates change over the form of economical and social development. In the early on or first phase of evolution nascence rates and mortality rates are high due to poor education, nutrition and healthcare. In such circumstances, characteristic of many developing countries prior to the Second World State of war, population growth remains low. As living standards, diet and public health improve during the 2d stage of the transition, mortality rates tend to refuse. As birth rates remain high, population growth becomes increasingly rapid. Historically, much of Africa, Asia and Latin America experienced this tendency during the 2d half of the twentieth century.

Over half the countries in the world, including many developing countries, have now entered the third stage of demographic transition. This is characterised by improvements in education and health forth with changes in technology, including the widespread availability of contraceptives, which give women greater selection. In this stage, urbanisation and greater female participation in the workforce reduces the economic and social benefit of having children and raises the costs. In the 4th stage of the demographic transition, both mortality and nascence rates turn down to depression or stable levels and population growth begins to fall. Many developed countries have passed this stage and confront the prospect of zero or negative population growth. As this trend continues, countries feel a rapid decline in fertility, to below replacement level. The combination of rapidly falling fertility and continued increases in life expectancy leads to rapid increases in median ages, with these projected to double in all regions, except for Africa, in the catamenia to 2050.

iii.ii Gender and Evolution

Gender inequalities and unequal power relations skew the evolution procedure. In many developing countries women's opportunities for gainful forms of employment are limited to subsistence farming—often without full land ownership rights or access to credit and applied science that might alter production relations and female bargaining power. In many societies, women are confined either to secluded forms of home-based production that yield low returns, or to marginal jobs in the breezy economy where income is exceptionally low and working weather condition are poor. In addition women typically have to endure the "double burden" of employment and domestic work—the latter includes housework, preparing meals, fetching water and wood, and caring for children—amongst many other tasks.

A range of studies over the last four decades take shown that households do not automatically pool their resources, and that who earns and controls income tin brand a major difference to household well-existence. Numerous empirical studies examining the human relationship between women'due south marketplace work, infant feeding practices and child nutrition point that the children of mothers with higher incomes are amend nourished. In the gilt mining industry in Africa for example an increase in women'south wage earning opportunities has been shown to be associated with the removal of healthcare barriers, the halving of infant bloodshed rates—specially for girls—and a reduction in the acceptance charge per unit of domestic violence by 24%.

The distribution of benefits and burdens becomes more equitable when women have a stronger vocalization and more access to pedagogy and employment. Improving women's economic opportunities can bear witness a highly effective way to reduce poverty and improve women's relative position and that of their children. Ensuring that more than women are enrolled in education, can read, write and count, and have advisable skills for jobs are also likely to amend the overall well-being of households. Steps to tackle restrictive cultural norms and laws regarding women's teaching, participation in the labour force, ownership of land and other avails, inheritance rights, marriage and freedom to participate in society make important contributions in this regard.

Many of these initiatives are likely to interpret into specific sectoral priorities and policies—for example vocational training, access to inexpensive ship, and admission to saving and credit markets. Women are disadvantaged in the credit market place as they typically take no collateral. Innovative microfinance schemes have sought to overcome this by providing flexible loans on favourable terms, ofttimes requiring no collateral or with zilch involvement, for investment in small calibration productive activities—such every bit rearing chickens or a goat. The virtually well-known case is the Grameen Bank, which has been providing finance to poor Bangladeshis since the late 1970s. Past 2015 cumulative disbursement of loans exceeded $16 billion and the bank had provided loans to over seven million individuals, 97% of whom are women.

The participation of women in the workplace together with gender differences in pay, promotion and business leadership are important aspects of empowerment. Political representation and gender disparities in healthcare and education (frequently reflecting "boy preference" in many parts of the world) are also fundamental indicators of social progress. Since the introduction of the MDGs in 1990, women in many countries have made progress towards parity with men, although much more than still needs to exist done. Meaning progress has been fabricated in terms of tackling female infant mortality and enabling your girls to nourish school, although gross disparities between men and woman persist across the board. Despite some notable progress, and then as well exercise practices which fundamentally constrain women, such as female genital mutilation, which affects at least 125 million women in over 29 countries.

Less progress has been made in terms of women'southward employment in the labour market—especially in Asia where ground has actually been lost over the terminal 25 years. This may have far reaching implications across our business concern with fairness and gender justice. A recent speculative study suggests that advancing gender equality in the workplace could add as much equally $12 trillion to global Gdp past 2025 (assuming every country in the earth could match the performance of its fastest improving neighbour in terms of progress towards gender equality). While the advanced economies have the most to gain, developing countries and regions could expect to benefit from significant increases in income by 2025 including India ($0.vii trillion or xi% of GDP), Latin America ($1.1 trillion or xiv% of Gross domestic product), China ($2.v trillion or 12% of GDP), sub-Saharan Africa ($0.3 trillion or 12% of GDP), and the Heart East and Due north Africa ($0.6 trillion or 11% of Gdp) (amongst other countries and regions).

Knowing that education, health and nutrition, and gender equity—among other things—are important for development is just the start. Developing policies to tackle these issues is a major challenge. In many countries, for example, the failure of instruction systems chronicle to a lack of quality rather than quantity of resources spent. In Bharat example studies accept catalogued a number of problems including poorly trained and qualified teachers, mindless and repetitive learning experiences, lack of books and learning material, poor accountability of teachers and unions, schoolhouse days without formal activities, and high rates of absenteeism amid staff and students. Moreover, improving outcomes is more circuitous than finding money for school fees or budgets for teachers. Issues such as having appropriate dress for the walk to school or the availability of single sex toilets at schoolhouse tin can play a decisive part, especially for girls.

3.3 Agriculture and Food

Agronomics provides the main source of income and employment for the 70% of the globe's poor that live in rural areas. The price and availability of food and agricultural products also dramatically shapes the diet and potential to buy staples for the urban poor.

Policies which discriminate against farmers and seek to create inexpensive urban nutrient by property down agricultural prices can perversely lead to rising poverty, specially where the majority of the poor are in the countryside. Low agricultural prices depress rural incomes, equally well equally the production and supply of food and agricultural products. The urban poor are even so more politically powerful than the rural poor, not least equally they are present in uppercase cities. An important contributor to the French Revolution of 1789 was the doubling of bread prices, and urban food protests have continued to pose a serious threat to governments.

Whereas in many developing countries farmers are discriminated against through price controls or restrictions on exports, which keep the price of their products artificially low, in many of the more advanced economies, and notably in the United States, European Wedlock and Japan, certain groups of farmers have achieved an extraordinarily protected position. Tariff barriers and quotas which restrict imports, together with production, input subsidies, tax exemptions and other incentives benefit a small group of privileged farmers at the expense of consumers and taxpayers in the avant-garde economies. This fundamentally undermines the prospects of farmers in developing countries, who are unable to export the products that they are competitive in. It also makes the prices of these products more volatile on global markets, as but a small share of global product is traded then that the international markets become the residual, onto which excess production is dumped.

An added crusade of instability is that the concentration of product in item geographic areas of the Us and Europe increases the bear on of weather related risks which exacerbates the instability in earth nutrient prices. Because farmers in many developing countries cannot export protected crops, they are compelled to concentrate their production in crops that are not produced in the advanced economies, and produce java, cocoa and other solely tropical agricultural commodities. This reduces diversification and leads to excessive specialisation in these commodities, depressing prices and raising the risks associated with monocultures. The levelling of the agricultural playing field, which has been a fundamental objective of the Doha Development Round of Merchandise Negotiations, which was initiated by the Earth Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, remains a central objective of evolution policy.

3.iv Infrastructure

Infrastructure is the basic physical and organisational structures and facilities required for the development of economies and societies. Infrastructure includes water and sanitation, electricity, transport (roads, railways and ports), irrigation and telecommunications. Infrastructure provides the fabric foundations for development. Investments in infrastructure tend to crave very large and indivisible financial outlays and regular maintenance. These investments shape the development of cities, markets and economies for generations and lock in particular patterns of urbanisation and water and energy use. Prudent investment in energy and transport infrastructure can have a meaning impact on environmental sustainability through ensuring lower emissions, college efficiency and resilience to climate change. Investment in sewerage and sanitation, as well as recycling of h2o, similarly has a vital role to play in reducing water-utilise and pollution.

Public individual partnerships tin play a major role, especially in urban areas and in telecommunications and free energy. Project finance and a range of other private investment structures are being used in a growing number of developing countries to encourage private investment in infrastructure. The outcomes have been decidedly mixed. In the United Kingdom, which has a reasonably sophisticated policy environs, public-private partnerships have been found by the National Audit office to provide poor value for money. In developing countries, post-obit the bankruptcies of toll roads in Mexico and water utilities in Argentina, lessons have been learnt and developing countries now account for well over one-half of the private investments in infrastructure globally. Given infrastructure demands and the shortage of adequate regime finance, there is a growing demand for private power, telecommunications and other infrastructure investors to finance construction and operations. The mixed experience in recent decades points to the need for caution and the establishment of independent and powerful regulators to protect consumer interests from what can become natural monopolies or oligopolies.

3.5 Legal Framework and Equity

Laws serve to shape societies and, in particular, affect the nature of the relationships of citizens to each other and to their governments. Legal frameworks include the "systems of rules and regulations, the norms that infuse them, and the means of adjudicating and enforcing them". The rule of constabulary has shaped evolution processes through the performance of laws, regulation and enforcement; enabled conditions and capacities necessary to development outcomes; and remained a core development end in itself. Therefore, the rule of law is of fundamental importance to evolution outcomes as it expresses and enables a guild's conception of social and economic justice, and more than specifically its attitudes to extreme poverty and deprivation. It also frames wealth, resource and power (re)distribution.

An effective legal and judicial organisation is an essential component for economical development, as it is for human development and basic civil liberties. Ensuring that decision making and justice are non determined by private favours or corruption and that all citizens have equal access to the rule of law is vital to overcoming inequality and social exclusion. It is likewise required for the creation of transparent and well-functioning financial and other markets.

The relationship between the legal arrangement and evolution is complex. In 1990, Douglas North and others pointed to a high positive correlation between the protection of property rights and long-term economical growth. Critics question whether the protection of belongings rights is a crusade or a consequence of economic development. In this respect several studies take shown that access to legal information and the dominion of constabulary can enhance participation and promote socio-economic development by empowering the poor and marginalised, to claim rights, take advantage of economic and social opportunities and resist exploitation. The law and the courts can play an important role in defining identity and guaranteeing economical and social opportunities. The dominion of law can improve admission to service delivery by reallocating rights, privileges, duties and powers. Strengthening legal institutions that prevent violence and crimes that undermine the well-being of citizens promotes development.

Legal institutions that promote accountability and transparency, and adjourn corruption can similarly facilitate development. Consistent and fair regulation and dispute resolution facilitates the smooth operation of the market system, and reduces the opportunities for corruption, nepotism and rent seeking. The rule of constabulary tin can as well protect the surroundings and natural resources and promote sustainable development by enshrining workers, social and ecology rights in constitutions and legislation.

4 The Future of Evolution

Over the past 75 years ideas well-nigh the responsibility of development have shifted from the colonial and patronising view that poor countries were incapable of developing on their own and required the guidance and help of the rich colonial powers, to a view that each country has a principal responsibility over its own evolution aims and outcomes and that development cannot exist imposed from outside. Withal, while both simple colonial and Marxist ideas of the interplay of advanced and developing countries are discredited, strange powers and the international community tin can still exercise a profoundly positive or negative bear on on evolution. This goes well beyond development aid as international trade, investment, security, ecology and other policies are typically more than important. The quantity and quality of assistance, the type of aid, as well as its predictability and alignment with national objectives nevertheless can play a vital role in contributing to development outcomes, particularly for low income countries and the least developed economies. Access to advisable technologies and capacity building helps to lay the foundation for improved livelihoods. So although evolution is something which countries and citizens must practice for themselves, the extent to which the international community is facilitating or frustrating development continues to influence and even at times dramatically shape development trajectories.

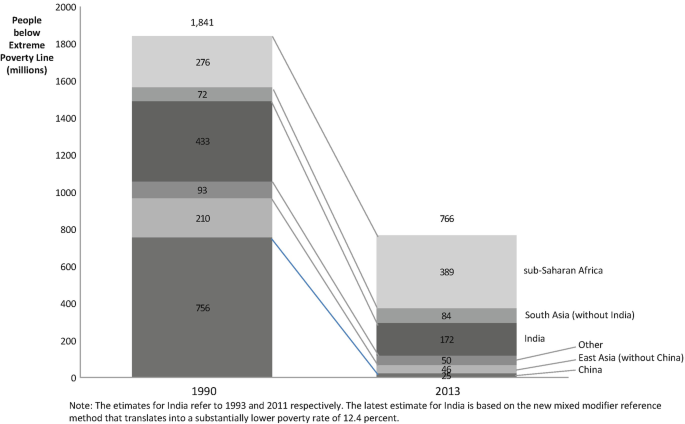

The extraordinary progress fabricated in poverty reduction is prove that development does happen. As is evident in Fig. 1, the number of people living nether $1.25 a day (at 2005 PPP) brutal past almost 900 million between 1990 and 2011, even though the population of developing countries increased past over two billion over the same period. Much of this pass up is attributable to the progress made in China, and to a lesser extent East asia and India. The greatest development claiming remains in sub-Saharan Africa. We showed earlier that, particularly for the poorest countries, aid remains central to development efforts, but that assist as well plays a vital role in other countries and in addressing public appurtenances.

People living on less than $1.90 per day by region (1990–2013). Source: Ian Goldin, Development: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2018. (Reprinted with kind permission past © Oxford University Press 2018. All Rights Reserved.)

The latest poverty estimates for 2015 point to a further reduction in the number of people living below the $1.25 poverty line, to around 835 million, the vast majority of whom go along to be located in South Asia (310 million) and sub-Saharan Africa (383 million). By 2030 the number of people living beneath the $i.25 poverty line is projected to halve again (to effectually 411 million), with the vast bulk of gains being made in South Asia where 286 million people are expected to escape extreme poverty.

In October 2015, the World Bank introduced a new "extreme poverty" line of $1.90 per twenty-four hours at 2011 PPP. The new poverty line has implications for the number of people classified every bit poor and implies re-estimating historical poverty rates (Table one). The latest headline figure for 2012—the most recent yr for which globally comparable data is available—suggests that close to 900 one thousand thousand people (or 12.8% of the global population) alive in extreme poverty. The majority are located in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, and to a lesser extent in South East asia. Although global income poverty has been reduced dramatically (irrespective of the poverty line adopted), it important to remember that progress on many of the social indicators featured in the MDGs and SDGs has been slower.

It is now widely recognised that while governments must set up the stage and invest in infrastructure, health, educational activity and other public goods, the private sector is the engine of growth and task creation.

The coherence of aid and other policies is an important consideration. For example, supporting agricultural systems in developing countries requires not only investments in rural roads and irrigation, simply as well support for international research which volition provide improved seeds, merchandise reform which allows admission to crops, and actions which will terminate the devastating impact of climate change on agricultural systems in many of the poorest countries. Equally noted before, the establishment of a level playing field for trade, and in detail the reduction of the agricultural subsidies and tariff and non-tariff barriers in rich countries that severely discriminates confronting agricultural development and increase food price instability, would provide a greater impetus for many developing countries than aid. Not all trade is good, and the prevention of small artillery merchandise, toxic waste product, slave and sex trafficking and other illicit trade should be curtailed and abuse dealt with decisively. The prevention of transfer pricing and of tax abstention is important in edifice a audio revenue base which provides the ways for governments to invest in infrastructure and health, pedagogy and other systems which provide the foundation for development.

The provision of global public goods, for instance by improving the availability, price and effectiveness of vaccinations and drugs, especially against tropical diseases and the treatment of HIV/AIDS, is a similarly important contribution for the international community. The cosmos of an intellectual holding authorities that allows for affordable drugs and the encouragement of research on drugs and technologies that foster development, not least in agriculture, is some other essential part for the international community.

The international community has a key part to play in the protection and restoration of the global commons, not least with respect to climate change and the environment. The establishment of global security and the implementation of agreements which seek to preclude genocide and facilitate the safety movement and fair treatment of migrants and refugees is another key responsibility of the international customs. So too is the prevention of systemic risks. Poor people and poor countries are most vulnerable to all forms of risk, and so international efforts to reduce systemic risks which pour over national borders is some other expanse which requires the coming together of the international customs.

Development is a national responsibility, but in an increasingly integrated world the international community has a greater responsibility to help manage the global commons as an increasing share of problems spill over national borders. All countries of the world share a commonage responsibility for the planet, but the bigger and more advanced the state, the larger the share of this responsibility that it is capable of shouldering.

iv.i Our Common Future

As individuals get wealthier and escape poverty the choices they make increasingly impact on others. The tension betwixt individual selection and collective outcomes is not new, with the study of the management of commons going back at least 500 years. Commons were shared lands, rivers or other natural resources over which citizens had access. In England, the rights of access became defined in common law. Many of these rights were removed in the enclosure movement which in the 18 century converted most of the mutual lands into private property.

The tragedy of the eatables refers to the overexploitation of common resources. Early examples include the overfishing of rivers, overgrazing of village fields or depletion of underground h2o. The management of the eatables has led to the development of customary and more than recently legally enforceable rules and regulations which limit the exploitation of shared resource. In recent decades notwithstanding, the pressure on common resources, and in particular on the global eatables, has grown with population and incomes. The global commons refers to the globe's shared natural resource, and includes the oceans, temper, Polar Regions and outer space.

Development has meant that we are moving from a world of barely 500 1000000 middle class consumers in the 1980s to a globe of over 4 billion middle course consumers in the coming decade. This triumph of development is a cause for celebration. But it provides a source for growing alarm about our ability to cooperate and coexist in a sustainable manner on our beautiful planet. Greater individual selection is for many regarded as a primal objective and effect of development processes. Other outcomes include increasing life expectancy, higher incomes and ascent consumption. Development has resulted in rapid population growth—two billion more people over the by 25 years with a further two billion plus expected by 2050. And globalisation has seen not only more connectivity merely too an increment in the global flows of goods and services, with the sourcing of products and services from more than distant places. The pressure on scarce resource has never been greater. Nor has the difficulty of managing them.

The upshot is a sharp rise in the challenge of managing the global eatables, coupled with the ascension of new commonage challenges. Antibiotic resistance is one of these new challenges. While information technology is rational for individuals to take antibiotics to defeat infections, the more that people have antibiotics, the higher the risk of resistance. When combined with the growing use of antibiotics in animals, at that place is an escalating hazard of antibiotic resistance, which would lead to rapid declines in the effectiveness of antibiotics, with dramatically negative consequences on these essential components of modern medicine. Other examples of the tension betwixt our private choice and collective outcomes include the consumption of tuna and other fish which are threatened with extinction, or our private use of fossil fuel free energy and the resulting commonage implications for climate change.

As development raises income and consumption and increases connectivity, the spillover impact of individual actions grows. Many of these spillovers are positive. Show includes the shut correlation between urbanisation and development. When people come together they tin can do things that they could never achieve on their own. Nevertheless as incomes rise, so as well do the oft unintended negative spillover effects, with examples including obesity, diabetes, climate alter, antibody resistance and biodiversity loss. Rising inequality and the erosion of social cohesion are also growing risks.

As Sen has explained, a fundamental objective of development is freedom. Freedom to avert want and starvation, to overcome insecurity and bigotry, and to a higher place all to exist capable of achieving those things we take reason to value. But with this freedom comes new responsibilities. Our individual contribution to our shared outcomes and as guardians of future generations rises with our own development. If development is to exist realised for all people, now and in the future, information technology is vital that we as well develop every bit individuals. Nosotros demand to ensure that we are free of the ignorance of how our deportment interact with others. Development brings new responsibilities too as freedoms.

Bibliography

-

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2001). The colonial origins of comparative evolution: An empirical investigation. Colonialism and development. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1369–1401.

-

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. (2002). Reversal of fortune, geography and institutions in the making of the mod world income distribution. Quarterly Periodical of Economics, 117, 1231–1294.

-

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. (2014). Commonwealth does cause growth (NBER working paper 200004). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economical Research.

-

Adelman, I. (2006). Republic and evolution. In D. A. Clark (Ed.), The elgar companion to evolution studies (pp. 105–111). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

-

Anup, Due south. (2010). Poverty facts and stats, global issues. Accessed Oct 10, 2015, from http://www.globalissues.org/commodity/26/poverty-facts-and-stats#src2

-

Baumol, W. (1986). Productivity growth, convergence and welfare: What the long-run data says. American Economic Review, 76, 1072–1085.

-

Bundy, C. (1979). The rise and fall of the South African peasantry. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

-

Collier, P. (2008). The bottom billion: Why the poorest countries are failing and what can be washed about it. Resource endowments and the resources curse. New York: Oxford University Printing.

-

Cruz, Chiliad., Foster, J., Quillin, B., & Schellekens, P. (2015). Ending farthermost poverty and sharing prosperity: Progress and policies. No 101740. Policy Research Notes (PRNs), The World Bank, p. 6 and table 1.

-

Diamond, J. (1997). Guns, germs and steel: A short history of everybody for the last 13,000 years. Geographical explanations of development. London: Vintage.

-

Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (2003). Tropics, germs and crops: How endowments influence economic development. Journal of Budgetary Economics, 50(1), 3–30.

-

Frankel, J. (2010). The natural resource expletive. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economical Research.

-

Frankel, J., & Romer, D. (1999). Does merchandise cause growth? American Economics Review, 89(3), 379–399.

-

Goldin, I., & Reinert, K. (2012). Globalization for development: Meeting new challenges. Globalization and development. New York: Oxford Academy Printing.

-

Groningen Growth and Development Heart: Statistics on convergent and divergent growth beyond regions and countries, analysis of long-term growth (1870–2010) utilises bachelor data on Gdp per capita in 1990 United states$ from the Madison Projection Database, http://world wide web.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm (2013 version); the analysis of divergent growth patterns for the period 1960–2014 (including statistics for Ghana, South korea and People's republic of china) draws on bachelor data on GDP per capita in 2005 U.s.$ from the World Banking company, World Development Indicators (online). Accessed September 29, 2015, http://data.worldbank.org/

-

Hirschman, A. (1973). The changing tolerance for income inequality in the course of economic evolution. Inequality and evolution. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(4), 544–566.

-

Institute of Development Studies. (2010, September 12). Global poverty and the new bottom billion (Working paper, Sumner, A). Accessed October 10, 2015, from https://www.ids.air-conditioning.uk/files/dmfile/GlobalPovertyDataPaper1.pdf

-

Kuznets, S. (1955). Economic growth and income inequality. American Economic Review, 45, one–28.

-

Li, H., & Xu, Z. (2007). Economical convergence in seven Asian economies. Review of Development Economics, 11(3), 531–549.

-

Page, J. (MIT, 1994). The Due east Asian miracle: Four lessons for development policy. In Due south. Fischer & J. Rotemberg (Eds.), NBER macroeconomics transmission 1994 (pp. 219–282). Cambridge, MA. Accessed October 1, 2015, from http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11011.pdf

-

Parente, S., & Prescott, E. (1993). Changes in the wealth of nations. Quarterly Review, 17(ii), 3–xvi.

-

Rodrik, D., Subramanian, A., & Trebbi, F. (2004). Institutions rule: The primacy of institutions over integration and geography in economic development. Institutions and governance. Journal of Economic Growth, 9(2), 131–165.

-

Sachs, J. (1989). Developing country debt and the globe economy. Chicago: Academy of Chicago Press.

-

Sachs, J., & Warner, A. (1995). Economic convergence and economic policies. Relationship between trade and evolution. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Inquiry.

-

Sen, A. (1981). Poverty and famines: An essay on entitlement and deprivation. The role of ability and other factors. Oxford: Clarendon Printing.

-

Singh, A. (1995, February 8). "Close" vs. "Strategic" integration with the world economic system and the "Market Friendly Approach to Development" vs. "An Industrial Policy" (MPRA newspaper no. 53562). Accessed Oct 1, 2015, from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/53562/ane/MPRA_paper_53562.pdf

-

Solow, M. R. (1956, Feb). Uneven evolution and convergence. A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, seventy(1), 65–94.

-

Globe Bank, Development Research Group. PovcalNet: The online tool for poverty measurement, poverty and inequality. Accessed October xviii, 2015, from http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/alphabetize.htm?1

-

Earth Health Organisation. (2015, September 17). WHO/UNICEF report: Malaria MDG target achieved among sharp drop in cases and bloodshed, merely 3 billion people remain at risk. Joint WHO/UNICEF News Release. Accessed Oct 3, 2015, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/malaria-mdg-target/en/

Author information

Affiliations

Respective author

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/four.0/), which permits use, sharing, accommodation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were fabricated.

The images or other third political party material in this chapter are included in the affiliate'due south Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If cloth is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended utilize is not permitted past statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Reprints and Permissions

Copyright data

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this affiliate

Cite this chapter

Goldin, I. (2019). Why Exercise Some Countries Develop and Others Not?. In: Dobrescu, P. (eds) Development in Turbulent Times. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11361-2_2

Download commendation

- .RIS

- .ENW

- .BIB

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-iii-030-11361-2_2

-

Published:

-

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

-

Print ISBN: 978-three-030-11360-five

-

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-11361-2

-

eBook Packages: Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Source: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-030-11361-2_2

0 Response to "What Makes a Country Bad for Again"

Post a Comment